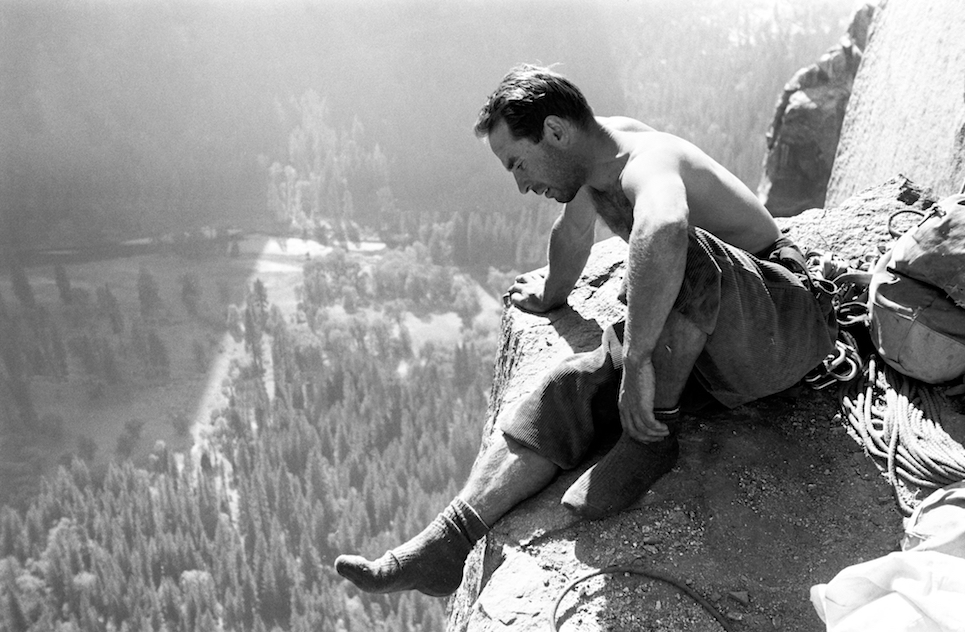

In the early 1970s, the American rock climber would be hard-pressed to find gear of any quality. In fact, he or she would probably have had to turn to Europe, where the nascent sport was more popular and companies were manufacturing equipment for it. “There were probably 250 climbers in the country,” Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard recalled with a chuckle in a recent interview with NPR.

But even if that climber chose to buy gear from Europe, it would likely have been low-quality, made of soft iron, the kind of equipment you use once and toss. Chouinard and his friends, following in the footsteps of transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Muir, believed they should climb the mountains but leave no trace behind. Pitons should not be used once and left wedged into rock. Discarded lengths of rope should not be left on the forest floor.

The same problem applied to sporting clothes. At that time, and especially for men, activewear consisted largely of sweatshirts and matching sweatpants. There were no clothes that made sense for people doing intense, outdoor activities.

Chouinard never wanted to be a businessman. “This was in the 60s, and businessmen were all greaseballs in the 60s,” Chouinard said at the Commonwealth Club of California in 2016. “We didn’t respect business. In fact, they were the enemy.” But he did have an innate sense that he could improve the tools he was using. “It’s just I have this knack that every time I look at a product I look at it and think, ‘well, I could make something better than that. It could be better,’” he said during an interview with NPR. This is exactly what Chouinard and his friends did. When they went climbing, they would return with ideas about how to improve their tools.

Soon, Chouinard realized that he could not avoid the obvious solution: build better equipment, make better clothes. So with that in mind, Chouinard got some books on blacksmithing and began to forge the gear that he and his friends wanted to use themselves. Soon, he was selling his pitons for a dollar and a half each, far more expensive than the European equivalent, but made to last. “I just happened to be a craftsman. Every time I looked at a piece of equipment I had an idea of how to make it better,” Chouinard said during a lecture at UCLA.

Soon, expansion happened. After a trip to the United Kingdom, where Chouinard saw a rugby-style shirt that seemed to fit the needs of climbers, he began importing sporting clothes and then designed and produced them himself. That was how Patagonia was born.

From there, Chouinard’s fledgling company began manufacturing a broad line of clothing meant specifically for sportspeople. Or more accurately, they began making clothes that Chouinard and his friends wanted to use themselves when they climbed and hiked and surfed. In reflecting on this time, Chouinard recalled trying to put himself in the shoes of his customer, hoping to come up with products that people didn’t yet know they wanted or needed.

The Uncharacteristic Entrepreneur

“If I get an idea, I immediately take a step forward and see how that feels. If it feels good, I take another step. If it feels bad, I take a step back,” Chouinard told NPR. This has been Chouinard’s approach since the start. At the beginning of Patagonia, he was neither an expert in manufacturing nor in apparel. In fact, Chouinard has no formal business training at all. He was simply a passionate sportsman–a person who just wanted to be outdoors and have clothes that made sense.

Chouinard is quick to admit that his not having the traditional background in running a major retail company has had positive and negative effects. “[I was] trying create a business that we wanted to come to work in. All of us. So that’s what we did,” he said in a talk at the Commonwealth Club of California. In all likelihood, that unfamiliarity with business and his wish to build something new helped Patagonia avoid some common traps fledgling companies fall into.

On the other hand, the same unfamiliarity led to some difficult situations, most notably in the 1980s, when about a decade after Patagonia’s founding, the company ran into trouble. “The market wanted our products, so we were growing 50% a year. But you can’t grow a business with 50% growth year after year on retained earnings. At some point, you’re going to crash,” Chouinard said at the Commonwealth Club of California. From the perspective of the long-term health of the company, Chouinard knew that such rapid growth was not sustainable.

For Chouinard, the goal was not simply growth. In fact, the way he saw it, the faster his business grew, the faster it would die. It was about making a change, about using environmentally friendly material and teaching people that you don’t throw out things, you repair them. Chouinard’s vision was that Patagonia would commit to owning one of its products forever. If something no longer fit, they would help sell it for you; if it broke, they would fix it; if it was really spent, they would recycle it.

At an early stage, Chouinard and Patagonia conducted studies on which materials were the friendliest for the environment (they were surprised to learn that 25% of all agricultural pesticides are used for cotton production) and adjusted their production accordingly. In light of what they found out about cotton, Patagonia started using 100% organic cotton in 1996. Chouinard wanted something lasting so that Patagonia could have an impact and exist far into the future. The same was so for the materials they used. After commissioning a study, they realized the impact of the cotton they were using. For Chouinard, such high growth would not take them to his goal.

To keep the company on track, Chouinard actually slowed growth, which with the addition of a recession, led to a critical moment for Patagonia. Chouinard didn’t know if the company would make it. Banks stopped lending the company money and revenues became tight. But with some tough decisions, including management level staff layoffs and an improved growth program that looked toward the future, Patagonia made it through. For Chouinard, there are two types of growth: that which leads to you being stronger and that which leads to you being fatter. Of course, he wanted the former.

In an interview with NPR, Chouinard reflected on entrepreneurship:

“One of my favorite quotes is:

‘If you want to understand entrepreneurship, study the juvenile delinquent because they’re saying this sucks and I want to do it my own way.’ That’s what the entrepreneur does. They just say, ‘This is wrong and I’m going to do it this other way,’ and that’s the fun part of a business. I love breaking the rules.”

It seems one rule that Chouinard has tried particularly hard to break is our modern consumer mannerisms. What is essential for Chouinard is that Patagonia offers a lifetime guarantee. In fact, it seems that the Patagonia mantra should be one of Chouinard’s core beliefs, which is to own very few but very good things.

Indeed, in a world where there exists an abundance of cheap clothing made with questionable materials by people in poor conditions–and our global problems are only growing–it seems we need more companies that share Chouinard and Patagonia’s mission.

Chouinard has never been interested in coming out with a cheap line of clothes. That is evident if you take a look at Patagonia’s online catalog. Despite Patagonia’s price points, Chouinard’s goal is not to reduce prices and appeal to a mass customer base like other retail stores. For him, good quality clothes which are made from responsible materials simply cost more. And we, as good consumers, should prioritize buying less but buying responsibly. That, Chouinard believes, will help us approach some of the daunting problems we face, which seems an idea that deserves reflection.

Patagonia Mission Statement

Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.

Wise words for the young entrepreneur

There is no doubt that Patagonia has a compelling story. What is now a company with reportedly over $600 million in revenue was started by Chouinard and his buddies because they wanted better sporting equipment.

Their impact on how we purchase and consume clothing and how clothing material is sourced is significant, perhaps even paradigm-shifting. But also worth discussing are the things we can learn from Chouinard’s approach to business.

Many have considered Chouinard’s style of managing his employees and a huge corporation as eccentric. In fact, many might have laughed at his company directive to hit the waves when the surf was up, or at his annual six-month vacation to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. But no one can argue with the outcomes, both in business but also in environmental impact and employee welfare.

In the early days of Patagonia, the company pioneered on-site childcare, flex-work based on a trust policy, paid maternity and other leave, coverage of healthcare premiums, and generous employee development programs. These benefits, of course, are still not entirely common in 2017, over forty years later.

What’s more, Chouinard took an unusual approach to staff his company. Most companies, as he points out, are strongly top-down. There are rigid corporate structures in place and hierarchies that determine how a company will operate. Patagonia, on the other hand, hired a bunch of young and independent people, and then left them alone. Chouinard recently mentioned that psychologists have come to study how the company manages to function so efficiently with this approach. Chouinard seems to bask in his unusual tactics. He doesn’t care when his employees work, so long as they get the job done.

For young entrepreneurs, Chouinard also gives some on-point advice. “If you want to be successful in business,” he recently said to NPR, “you don’t go up against Coca-Cola. They’ll kill you. You just do it differently. You figure out something that no one else has thought of and you do it in a totally different way. So, breaking the rules means you have to be creative.”

Above all, what seems to drive Chouinard the most is the wish for a simpler life. This can be seen in his approach to business, his slowing the growth of his own company, and his encouraging customers not to buy his products but to repair, reuse, and recycle.

Chouinard brings us a lot: wisdom about business, the environment, and how we as consumers should strive to better ourselves in a world that is being taxed by our needs and wants.

But perhaps most poignant are his words about life, which he recently said in an NPR interview:

“The hardest thing in the world is to simplify your life because everything pulls you to be more and more complex. I think what I have learned from fly-fishing is that if we have to–either we’re forced or we decide to–go to a simpler life, it’s not going to be an impoverished life; it’s going to be really rich.”

That too deserves some reflection.

You might also enjoy: