As a little girl, Sasha Fisher always wondered why the world she lived in was unequal. A world where some people were unable to meet their basic needs and couldn’t afford to live in dignity.

She always knew she wanted to change that — thus she decided to work with non-profit organizations.

Why non-profits?

Fisher explains that there are three ways of addressing world inequality.

These include:

- businesses,

- governments

- and non-profits.

The non-profit sector hasn’t matured as much as it needs to. She states, “Non-profits are all focused around human impact and that’s what I care about primarily. The question is the vehicle to get there.

Non-profits focus on human impact. Their mission is to impact the world’s population in a positive way. They don’t model the organization to have an income stream. They are people- and impact-motivated. She explains, “There is an opportunity to be as clear as possible about your mission and the impact you want to create without muddying it with compromise.”

Don’t be afraid to start young

In high school, Fisher became involved in fundraising for a non-profit organization with projects in Sierra Leone. In University, during her sophomore year, she joined a team of volunteers to South Sudan. Working with this international non-profit organization gave her first-hand experience dealing with critical development issues. She started young and was determined to make it at all costs.

Fisher realized that she had no way of knowing what type of aid was more or less effective. She asked herself, “What’s the difference between donating to one aid organization and another?” She had no clue. She believed this South Sudan opportunity would help her understand more about impact.

“There are some ratings online on Charity Navigator about a handful non-profit companies. But they don’t tell much about impact,” she adds.

It was an exciting opportunity for her because she would travel with the team to the field. The country director taught her a lot about the context and the region. She was shown around to other aid projects as well. She felt they were not being used effectively in an area that received a lot of aid money.

In South Sudan, Fisher realized that most non-profit organizations were not able to measure project impact.

Most of the aid projects were not being effectively utilized. Several aid organizations were letting the South Sudanese people sit on the sidelines. They did not involve them in the conversation on what was being built. Local communities had no ownership of the projects.

Related: How This Teacher Started a Social Change Business on The Side

Give communities control over their own future

Fisher felt that, considering the South Sudanese had fought for their freedom for more than two decades, they ought to be given control over their future.

They had the fundamental human right to define what the future held for them and their families, a quality that was lacking.

By the end of her volunteer period, she had one big question lingering in her mind, “Who was making the decisions on getting power to the hands of local communities and families?”

When Fisher graduated, she felt obligated to go to Rwanda, even though she had never been there.

She needed to go to a region that required foreign aid and Rwanda seemed like the perfect place for her.

Moving to the country was the least scary. Instead, she couldn’t stop thinking about how they could use their foreign aid money better. She couldn’t figure this out unless she was in the area receiving the aid money.

Her first steps involved locating a region with an operational local CBO. She started by learning from the organization, then piloted a project within the community. She deeply felt that local community had to drive and own local projects.

She says, “I didn’t want to be an expert at anything because the whole point was this: Whatever happens should be owned and driven by local communities.”

In the Rwandan villages, Fisher brainstormed with local partners to identify how best to support, launch, and implement their development programs.

After a lot of consultation and deliberation with government, businesse,s and non-profits, Spark MicroGrants was established in 2010

Support pre-existing non-profits

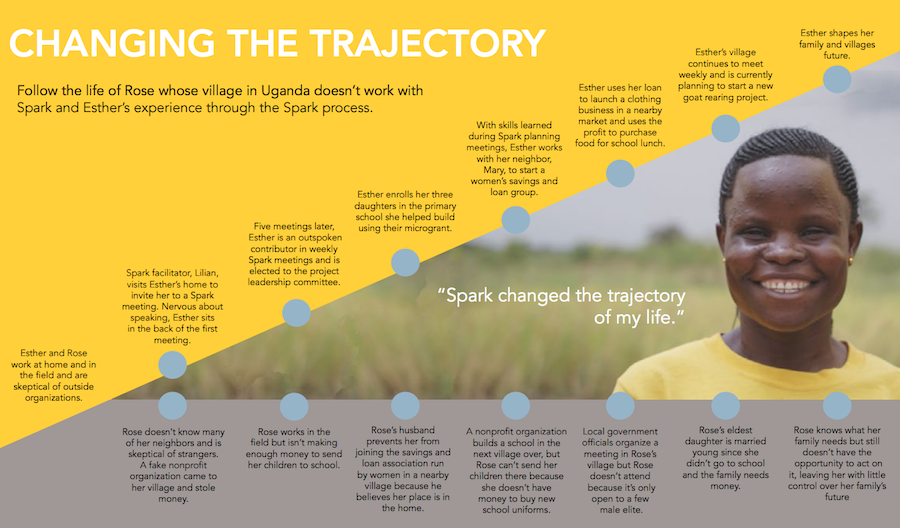

Fisher felt that Spark’s role should be supportive of the non-profits already on the ground. They could also act as a bridge between the villages and their government. The organization came up with a facilitation process paired with a seed grant provided directly to villages. This process is fully inclusive of gender and age. Community members make decisions about their welfare.

This furthers the main goal of helping the local community learn how to control their future. Helping them tap into their potential is a strong way to bring long-term change.

Spark works in collaboration with the Rwandan government to strengthen village leadership. Building community village elders that take charge of these projects is one of the main keys of Spark’s success. Spark goes into a village for only two years, so implementing the process correctly is the key to the long-term success of the village.

Focus on the process of your project if you want to succeed

The core process – from Spark first getting involved to finding seed funding — takes 6 months, after which implementation begins. This can last three to six months and Spark management support is always provided.

The focus is to bring the project to life, but an income earning component is often attached. This depends on the type of project the community selects.

Some of the projects that have been done include:

- Starting a mill where villagers pay to mill their cereals

- Sale of surplus crops from farming

Ninety percent of Spark-funded projects are still sustaining two years after launching

So, what’s the process?

MONTH 1

Within the first month, Spark MicroGrants goes into a village and conducts discussions for community building. The community identifies the right people, the direction to take, and problems to address.

MONTHS 2 & 3

Next is two months of goal setting. In the first month, the village discusses their history and enumerates their existing assets. It also addresses past projects.

In the second month, they identify the village they foresee and set goals to achieve it. They then brainstorm find pathways to reach the goals.

MONTHS 4 & 5

After that, proposal development starts, which takes two months. It includes a financial sustainment strategy in which the organization offers basic training on cash flow. The financial literacy includes skills that are kept simple and basic to ensure everyone understands.

Spark MicroGrants then explains the amount of funding provided to begin the project and how much is required to sustain it over time. Community members elect a village committee to manage the program and assign roles.

Transparency is imperative with Sparks as they are continually held accountable to their donors. In each village, the leaders have a responsibility to report fully on project finances. The report includes the specific amount of money received and the amount spent in the project. Transparency within the organization and villages enhances visibility on how money is spent and for what purpose.

MONTHS 6, 7, & 8

In the next three months, there is a technical review, management support, and future visioning.

The technical review process includes some training and technical specifications to address the set goals.

Future visioning involves building partnerships with local organizations and government officials. The whole idea here is to have a smooth process that enables the set goals to be carried out successfully.

The last step before the implementation is the disbursement of the village fund — $8,000 per village — with which to implement the project of their choice. The community is physically involved in the actual building of projects. The media, businesses, and local government personalities are invited to create awareness.

When dealing with projects that involve money and development, it’s all about the process. Therefore, Sparks puts in a lot of work into ensuring everything is done well, with pinpoint precision. This enables them to leave a long-lasting mark in a community.

Seventy-three percent of villages advocated for external support after working with Spark

Meet Gracie

On passion, learning, and raising money

When Fisher founded Spark MicroGrants, she knew very little about making money. All she knew was that she needed more money to reach more villages. She was so passionate about this.

In the initial years, there was a lot of learning to do because the fundraising experience she had was during high school and university. See, even if you have passion for something, you need to learn about ways to make it happen.

While in her senior year of university, Fisher asked several people to help out with funds. She wrote emails to several groups, which seemed like a crazy idea. To her surprise, two foundations based in New Jersey actually responded and donated some money. This was a big break for her, finally getting first donations to the organization. One of the foundations has grown with Spark MicroGrants and still funds them to over $100,000 to date.

In the first year of the organization’s operation, it started with $10,000. By 2016, they were able to raise $1.5 million which they leveraged for programs and other organization uses. Currently, the organization obtains funding from individuals, foundations, and corporates, among other donors. They have a huge group of sponsors willing to chip in and sponsor villages.

It costs $10,000 to fund a village through this process. From this amount, a village chooses its own project. For every project the organization institutes, a second project is launched independently.

From deep passion and learning, Spark was able to beat the odds and raise the cash needed to get going.

Setting out to be different and to keep growing

From the beginning, Spark MicroGrants set out to be different.

It designed a new approach that moved away from the traditional problem-solving framework to focus on goals. In the beginning, the grants were based on projects but the company has now streamlined the grant to a village grant.

Every village receives the same amount of money so there is no competition to get more.

In the first village in Rwanda, the Spark’s core process took three months. This period has changed, evolved with feedback from families. It has currently grown to a six-month process with a two-year follow on support. This includes quarterly check-ins per village.

How do they make decisions?

Decision making is based on impact. To avoid corruption, Spark establishes clear accountability to the villages they serve. Its mission is to support communities and improve local conditions. It has an efficient system, designed to achieve that in the best way possible.

There is a lot of prescriptive aid and Spark MicroGrants seeks to change this. Its model pushes the limit on how much ownership and decisions the people being served can be left with. It believes that all the decisions should belong to the people.

The project process is cyclical. Every year, there is something new to tackle within the village. The village goes through strategic planning on the future, which is reviewed every year. This process ensures the village is leaping back while looking forward.

From Rwanda, Spark MicroGrants has grown to Burundi, Congo, Ghana, and DRC. In these countries, they have partnered with more than 150 villages. Of all the village projects facilitated by Spark, 94 percent are self-sustaining and 77 percent have birthed other projects without Spark’s support. Over 90 percent of these continue to meet regularly and discuss important community issues.

Helping people to achieve the future they want

Spark MicroGrants has been working in Rwanda for seven years now. Over 56 community partners have been facilitated with Spark staff. The organization has helped villagers create a system of agreeing on ideas, building a plan for execution, and managing their own projects.

Collective weekly meetings are held where village families in the communities plan for the future they want. The project ideas originate from the families, who then work on them together.

Spark was founded to get resources to the hands of families they sought to support. They do this without viewing them as beneficiaries. This approach is different because they encourage communities to seek their own solutions. It trusts people with their own future.

This shows how organizations can support community members better. There has been great feedback from families in the supported villages. This include progress in goal setting and government advocacy. Spark constantly listens to feedback from villages on how to improve the system.

Actionable Steps and Takeaways

- Be willing to move out of your comfort zone. Traveling and experiencing the world can create powerful inspiration but change also starts where you are. You don’t have to move to Rwanda to find problems worth addressing.

- Being entrepreneurial doesn’t always mean building your own organization. You can get your innovations incorporated into existing institutions. “The best teams are full of entrepreneurs working together with complementary skill sets and ways of thinking to build a larger scale movement,” Fisher says.

- Every human being has a cause. Something they feel passionately about. Fisher always knew her niche was human impact and that non-profits were the best way to achieve that. What do you have and how can you get it to the people?

- Work with the people whom you are serving to solve problems and build long-term solutions into your processes.