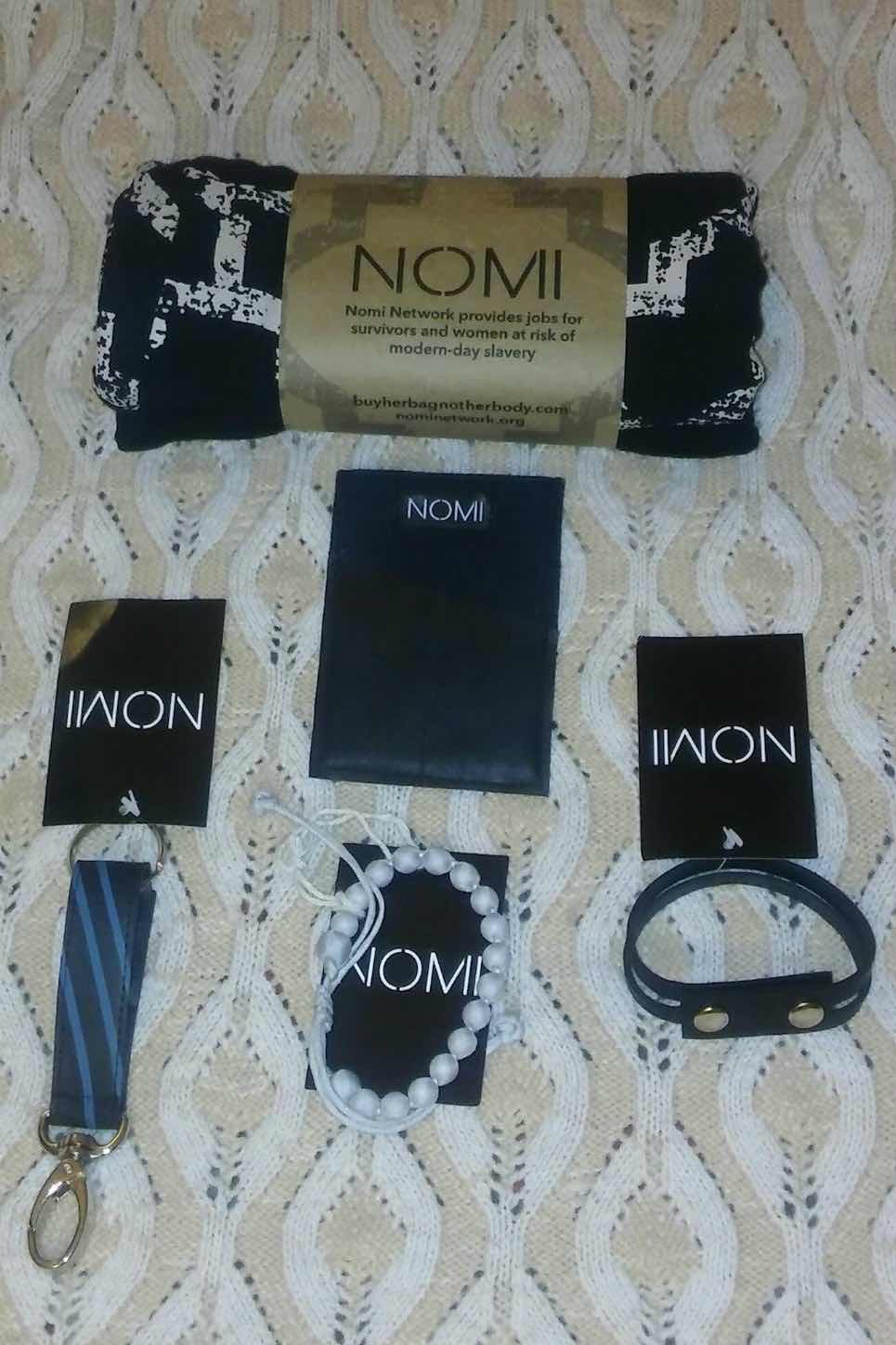

I found out about Nomi Network because I lived a block away from co-founder Alissa Ayako Williams from 2011 to 2013. She shared with me and other neighbors ways we could be abolitionists in the fight against modern-day slavery: purchasing slave-free goods, donating to organizations working against slavery and raising awareness about human trafficking. I visited the Nomi Network pop-up holiday shop at Union Square in Manhattan then and have since collected an array of their products made by women who have survived or are at risk for human trafficking.

Why I Choose Nomi Network

I am also adding items from Nomi Network to my merch table when I have solo music gigs. By connecting workers, designers, retailers, and consumers, Nomi Network is chipping away at the problem of the horrific $150 billion illegal industry of trafficking 46 million people through their presence in urban Cambodia, in rural India, and at conferences concerned with the impact of the global fashion industry.

“You have all heard that it takes a village to raise a child, I believe it takes a network to end modern-day slavery.” Diana Mao, Co-Founder and President.

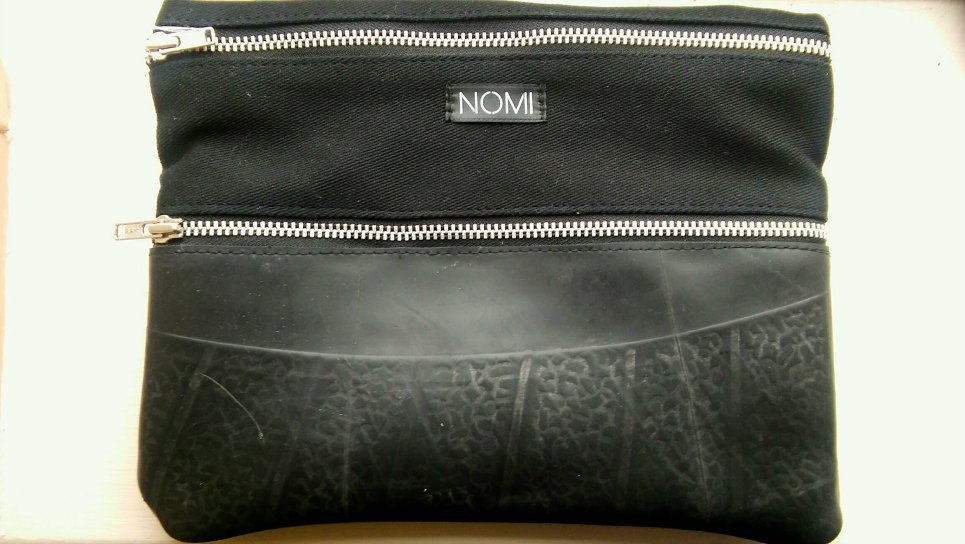

Having sourced recycled materials from its beginnings, one of Nomi Network’s newest product lines features accessories made from upcycled tires in Cambodia. Although the country has more of the natural resource rubber than it has tire manufacturing facilities, scrap tires can serve as breeding grounds for disease-causing mosquitoes and present a risk of long-burning fires that pollute the air, soil, and water.

Each item in the collection is handmade and preserves the grooves and unique patterns of wear from the tires. According to Princy Prasad, Nomi Network’s sales manager,

“My personal favorite aspect of the collection is that we do not alter it at all…. An item once discarded, but suddenly [it] gets a second life. That is the best kind of recycling.”

Rubber is part of Cambodia’s long history of agricultural trade. The first centuries of Cambodia’s history included irrigated rice-growing, rule by Buddhist or Hindu kings, and commerce and power struggles with China, Thailand, and Vietnam. The country was a French protectorate from 1863-1953. France established rubber plantations in eastern Cambodia in the 1920s. Similar to Cambodia’s ancient regional commercial relationship, policies and investment from China, Thailand, and Vietnam significantly impact the contemporary rubber industry.

Although rubber continues to be the country’s second-biggest export (after rice), fluctuating prices in recent years have led to clearing land for new rubber plantations in areas previously used for growing food and ecological conservation. Creating plantations and processing the rubber increase the amount of carbon and nitrous oxide in the air. This dramatic change in land use has led to disagreements between villagers living in or near potential sites for new plantations, foreign and domestic business owners, and government authorities.

As of 2011, rubber maintained a consistent place among Cambodia’s industries, while textile, wearing apparel, and footwear manufacturing had overtaken all sectors except agriculture. There are currently 600,000 Cambodian workers in the garment industry. The government and the International Labour Organization are collaborating to improve wages and working conditions. Yet, some of these workers are victims of human trafficking.

Human Trafficking in Cambodia: A Short History

The poverty that causes human trafficking in Cambodia dates back to 1970s. After gaining peaceful independence from France in 1953, Cambodia became entrenched in the Cold War, climaxing during the Vietnam War with violence between the government’s Khmer Republic and the communist Khmer Rouge. When the Khmer Rouge took power, they killed 1.7 million people and expelled city residents to rural agricultural work.

Although the Khmer Rouge was overthrown in 1979, the 1980s were filled with guerilla warfare between opposing factions as human and economic systems languished. Through U.N. support starting in 1991, a three-party coalition government was established in 1993. The new millennium began with tensions continuing among the political parties as Khmer Rouge leaders were tried for genocide and crimes against humanity. Although the government passed a series of initiatives for labor, industrial development, women’s empowerment, and social protections by 2015, executing them all is a complex and long-term process.

Meanwhile, every stage of human trafficking happens in Cambodia: victims are taken from, taken through, and taken to the country. 201,000 Cambodians are in forced labor, predominantly as fishermen, garment workers, domestic workers, and sex workers. While policies exist to reduce trafficking, local enforcement varies, and the majority of work for survivors is done by NGOs. Nomi Network is one of them.

Nomi Network

Co-Founders Diana Mao, Alissa Ayako Williams, and Supei Liu named Nomi Network after an eight-year-old survivor of sex trafficking they met in Cambodia. The non-profit launched in 2009 to provide training and job opportunities for survivors and women at risk of trafficking.

Their first partnership with an organization serving these women employed 23 in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. By 2012, they grew to support 80 women and established a product line with tote bags and electronics cases made from recycled rice sacks.

Their model continued to partner with shelters for survivors and social enterprises, employing 400 in Phnom Penh in 2014 as they provided training in design, quality control, and marketing. The next year, they assisted more organizations in developing product lines and investing in equipment.

In 2016, their offices in Cambodia began to include a comprehensive in-house education program: Nomi International Fashion Training Program. It helps workers refine their skills in reading and executing spec sheets as well as providing classes for entrepreneurs in market access, logistics, and personal development. The program also hosts networking events between U.S. retailers and Cambodian social enterprises. Nomi Network is positioning themselves to foster Cambodians not only as well-paid and well-treated producers of garments but as fashion industry leaders.

Since 2012, Nomi Network has also worked extensively in Bihar, India, a state where the caste system has significantly contributed to the 70% poverty rate.

“When a woman leaves our programs, we want them to be able to stand on their own two feet, with the tools and resources we provide. The same goes for how we work…because we hope that instead of adding to the carbon footprint, greenhouse gases, or negative impact…we change it with the positive and support a business that ushers in that change.” Princy Prasad, Sales Manager.

Helping to raise awareness and make money.

In addition to their job training, the online marketplace, and pop-up shops, Nomi Network raises awareness and advocates for ending modern-day slavery and for making supply chains sustainable. They present about forced labor, child labor, and supply chain transparency to major retailers and brands. They have sponsored a design competition at Parsons School of Design in which students design products using recycled materials and ethical production methods. They have led discussions at the UN, the White House, and the Concordia Summit.

Although less than 10 years old, Nomi is stopping generational cycles of poverty. Women whose families once sold or threatened to sell them are able to earn a living and keep their children in school. Workers have consistent livelihoods and a few have earned enough to attend college. Thousands of people have been impacted by their training and advocacy.

If you want to buy one of their products, check out this beautiful pillow now!